Related Stories

Interactions Stories

What's for Dinner?

Southern aquaculture, especially catfish farming in Mississippi, faces significant challenges from migratory waterbirds, particularly the double-crested cormorant. These birds, attracted by the dense fish populations in aquaculture ponds, cause millions of dollars in losses each year. A study by Dr. Brian Davis and his team found that cormorants consume up to $12 million in catfish annually, and when factoring in bird deterrent costs, the total financial impact is around $64.7 million per year. While various methods, like disrupting bird roosts, have been tried, there is no perfect solution. Research is ongoing, with new methods, such as drones, being explored.

Additionally, a study on scaup ducks found that their impact on fish farms varies with the season, suggesting farmers should focus on bird management during colder months when ducks are more likely to consume fish. Davis emphasizes the need for continuous research and evolving management practices to address these conflicts as the aquaculture industry grows.

2023

Monitoring Resistance

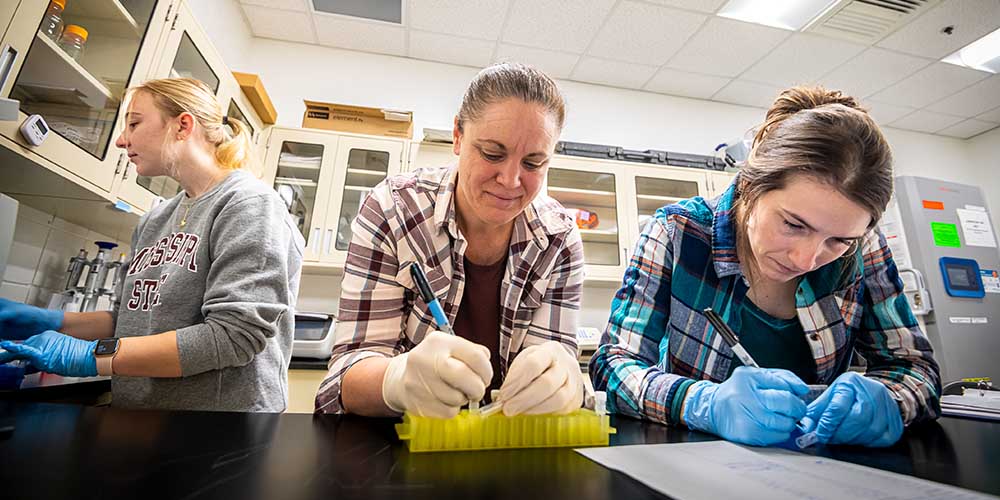

Dr. Dana Morin, a wildlife assistant professor at Mississippi State, is studying the role of wildlife in the spread of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), which makes infections harder to treat. AMR can be transmitted through bacteria, fungi, and other pathogens that evolve resistance to medications. Morin is focusing on how species like black bears, deer, and ducks, with their diverse ecologies and interactions with humans, could spread AMR. She collaborates with Dr. John Brooks from the USDA to analyze bacterial cultures and DNA from animal fecal samples, investigating genes linked to AMR. Additionally, Morin is exploring the use of dung beetles as a cost-effective method for identifying AMR hotspots in the environment.

Her research aims to understand how wildlife movements and human interactions contribute to the spread of AMR, ultimately helping predict and prevent its transmission.

2023

Understanding Deer's Flight Response to Avoid Vehicle Collision

In the U.S., deer/vehicle collisions cause 1.5 million motor vehicle accidents each year, resulting in 200 fatalities and over a billion dollars in property damage. That's why an FWRC scientist, with lead collaborators from participating agencies, sought to better understand how deer respond to approaching vehicles before a collision occurs. Dr. Ray Iglay, assistant professor in the Department of Wildlife, Fisheries and Aquaculture and FWRC researcher, was part of a team that evaluated deer responses to approaching vehicles. The aim of the team was ultimately to decide how the deer responded to different threats, whether they would go across the road or away from the road. The team conducted an opportunistic experiment protocol, recording observations of deer during a six-month period on two lane roads with maximum speeds of 40 miles per hour.

The researchers studied flight initiation distance (FID) or the distance from an approaching predator at which the prey flees. The team recorded 328 vehicle approaches toward groups of an average of two deer. While the team found that proximity to the road influenced FID, deer didn't demonstrate spatial or temporal safety thresholds and FID wasn't impacted by either oncoming vehicle speed or environmental conditions. The team also found that road crossing was influenced by group size and proximity to the road. Collaborators include Dr. Morgan Pfeiffer, Dr. Bradley Blackwell, and Mr. Thomas Seamans, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS); Dr. Travis Devault, Savannah River Ecology Laboratory, University of Georgia; Wildlife Services, National Wildlife Research Center, and the Ohio Field Station.

This research is funded by FWRC and U.S.D.A. Wildlife Services National Wildlife Research Center.